What does it mean to be human

evolutionary biology and existential poetry (in very layman but scientific grounded)

This essay explores the absurd yet inevitable emergence of grief, love, and belief through the lens of evolution. From bacteria committing molecular suicide to elephants pausing to grieve, we trace how traits selected for survival accidentally gave rise to meaning, madness, and self-fulfilling beliefs.

This article is to formulate an argument that:

If you know what you want and you will suffer less / Knowing what you want will alleviate your suffering.

You are a creature starved for meaning and problems to solve derived from our very own biological edge to survive.

Trust is the highest valuable currency a human can exchange.

You are influenced by what you hear and what you chose to believe. Which is fortunately, very malleable.

Table of Contents

Meet Phylliroe

Meet the holland lop, more well known as the dumbass

Shark, the apex predator

Meet the Nudibranch

Biological Edge

The Lazy Panda

Human Prisons

Symptoms from Biological Edge

Elephant’s Solidarity

Meet the Nazca Booby

“Keep Trying Until its as Good as it Gets”

Penguins that Loved

Grief as the symptom of love

Something of Importance

Chemical Reactions under the Heroic Curtain of Self Sacrifice

“I” Keep Living

Symptoms from a Biological Edge: The Bacteria's Curtain Call

The Energy to Fuel Tears

rom Molecules to Memory: When the Symptom Learns to Feel

Murder as the Inevitable Natural Order

Enter the Dodo

The Tasmanian Tiger

Fear of Death that Drives Learning

The Rise of the Anxious Killer

Fear of Something Bigger than Ourselves

Impact of Beliefs

Identity, Purpose, and The Illusion of Agency

The Most Beautiful Symptom of All

Meet Phylliroe

Strange as it seems, Phylliroe is a type of sea slug that will serve as a crucial component in the argument, but in order to get from there, we would need to explore how such seemingly oxheaded fish with bioluminescence insides could live and not die and why some species went extinct.

Species that wants to survive will need to tick a very biological tickbox of being able to take in resources available around them, be as efficient as it could in the process as a mean to convert those resources into energy, and be “favorable” enough that it will win in courtship in inter-species competition in order to be able to pass its gene so that the species gene pool flourish for generations to come.

Species that are not able to tick this box will die and eventually extinct. Never to be known again, or at least die in a fast burial with low oxygen level and stable geological condition and has poor microbial activity then it will be remembered on the fossil records. Oh but fossils are estimated to only represent less than 1% of all species that have ever lived on Earth. So never to be known again is actually the more likely outcome.

Anyhow, good thing that we can still learn from both what still exists and what has extinct.

There’s a fascinating play that happens that species do to avoid extinction, and it’s an interplay between the species with its environment. Note that every species needs to somehow be able to consume a good enough amount of resources to reproduce, but more often than not, there are competitions for the species that compete for the same exact resources. For example—a rabbit.

Can you think of how many species feast off a rabbit? Hawks, foxes, snakes, coyotes, even humans. And from the perspective of a rabbit that eats grass, how many species compete with the rabbit to eat that same grass? Deer, sheep, cows, insects, and other grazers all tug at the same food supply. If all the grass is chewed out, what must the rabbit do then?

Meet the holland lop, more well known as the dumbass.

Do you think this dumbass just spawned in the wild? That it gracefully hops through the forest, dodging predators, foraging with finesse, thriving on instincts honed through millennia of natural selection?

Absolutely not.

We engineered the living shit out of it.

Through careful and selective breeding, we managed to formulate what I personally think is the best and cutest bunny breed ever. Big head. Tiny body. Ears like soggy croissants. Built like a living plush toy. This breed was hand-crafted—bred in cages, pampered, protected, and praised—not by nature, but by human preference.

It didn’t fight to survive. It got voted into existence by a group of humans pointing and going “Awwww.”

Now imagine putting Dumbass in the wild.

Zero skills. No survival instinct. It might try to befriend a fox. It might try to eat plastic. It might just sit and wait to be fed because that’s how it’s always been. You think the hawk circling above gives a damn about your cuteness rating? Nope. Gone in sixty seconds. Maybe less.

Though I personally wouldn’t put dumbass in the wild knowing my experience having it as a pet. Its vision is so bad it sometimes doesn’t even register that I’m only a few feet beside it, let alone imagining myself as the hawk ready to pounce dumbass.

You know what I would be comfortable to be put in the wild?

The picture even speaks for itself, the long legs build like a spring for prime agility and eyes with crystallzed vision of the souls of its brethren that it is sharp as ever to avoid any nonsense that is reaching to it.

There’s a REASON why we are able to domesticate rabbits to the point that it has become a fluffy couch potato with anxiety issues.

Because rabbits, biologically speaking, are soft targets. They’ve always been prey animals. Their main evolutionary skillset?

Hide.

Multiply.

Hope they’re not the slowest in the group.

So when humans came along like,

“Hey what if we fed you and made you cuter?”

the rabbit’s were like:

“Deal. I wasn’t doing great anyway…”

So then we took wild European rabbits (Oryctolagus cuniculus), and starting around 1,400 years ago—that’s the 6th century AD—a group of French monks decided, “You know what? These would make excellent loophole meat.” See, the church had banned eating meat during Lent, but rabbit fetuses were technically considered “fish-like” and therefore acceptable.

So, the monks got to work. They started selectively breeding rabbits in captivity—not for survival, not for intelligence, not even for dignity, but for convenience. Over the next 1400 years, we have holland lops with its giant ears! Yay! Very cute and wholesome!

p.s they can be so easily stressed out in your house, so stressed that they can die, so please handle with care and love and affection as much as possible.

Anyhow, imagine 1400 we did that with a hare instead of a rabbit…

Here’s the thing, hares are a whole different beast. You can’t domesticate them for three reasons:

They don’t trust you.

They have the cardio of a marathon god.

They’re already better at surviving without you.

Born with eyes open. Legs built for runway takeoff. Brain wired for paranoia. A hare will yeet itself into a bush at the sound of your breathing.

They don’t dig cozy burrows like rabbits. They nest in grass. Out in the open. Relying 100% on awareness, speed, and nerves of steel. They're not waiting for predators to find them. They're already gone.

Shark, the apex predator

Where there is a niche to be filled—There will already an animal that fills it. Nature doesn’t leave an empty gap open. - me

Actually Aristoteles said that, but he said it more like:

“Nature abhors a vacuum.”

He meant that in nature, emptiness doesn’t last. If there’s a gap, a space, a niche—something will fill it. Fast.

And if it’s not you? Tough luck. Something else will evolve to do it better, faster, and with more aerodynamic fins.

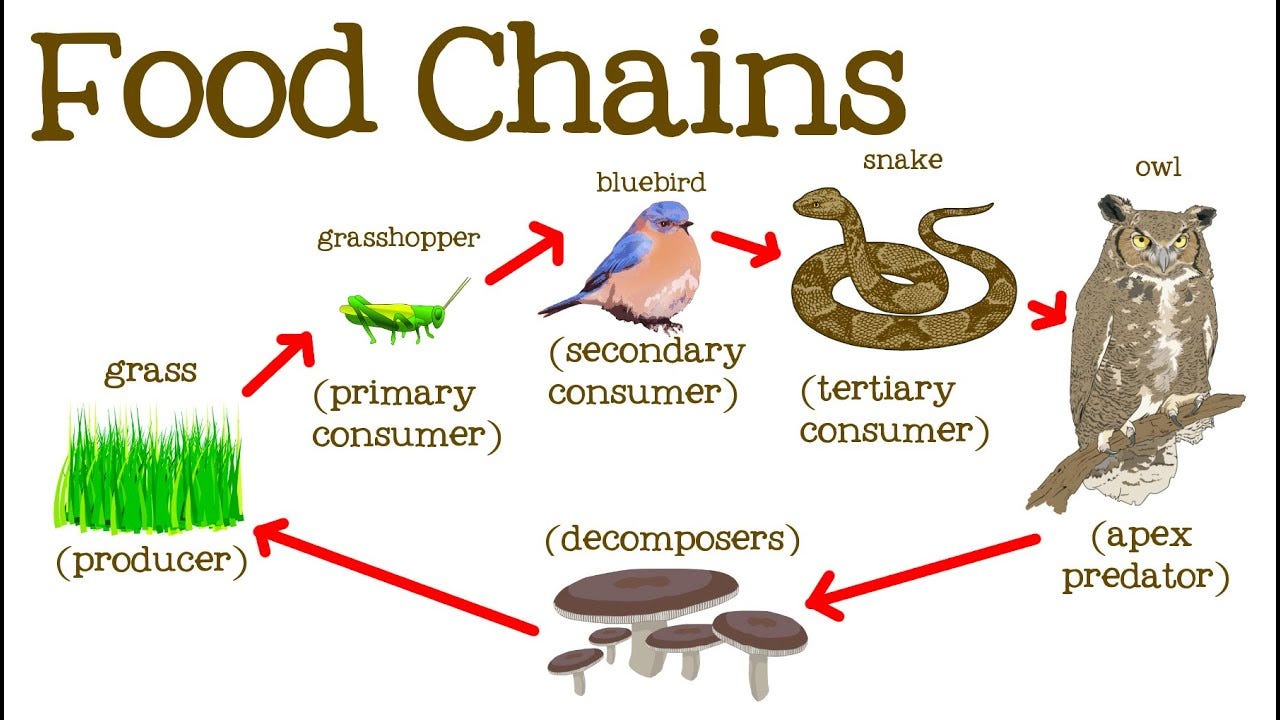

So when we see like you know that diagram, the one that you see on 3rd grade or so. Ah yeah, its called the food chain diagram.

See right, on this oversimplification of food chain, there lies a species that fills a role on the whole ecosystem and this ever seemingly perfect condition is not carved in stone, but rather is dynamic as the environment grows. For example, we have a term of “invasive species” where somehow a new species say migrate to the environment and now it disrupts the food chain. Imagine a herd of wild foxes just came by to the area!

and yk what they do? They do fuck all.

They eat the birds. Easy prey. Ground nesters? Gone.

They eat the grasshoppers too, just for the protein crunch.

They snatch up the snakes if they can catch them, and even mess with owl eggs if they’re feeling spicy.

FUCKING MOGGED.

Now what the other species need to do? They need to up their game man (as a species). But get this, GENETIC MUTATION ALWAYS HAPPENS, thats why we have albanism, sometimes we have 6 fingers, blue eyes, lactose chugging ability, down syndrome, heterochromia, sometimes we have no Fingerprints, gigantism, any much much more. But the important line is it always happens and it doesnt care about you necesarrily, it doesn’t care about the individual, the individual is always the guinea pig.

It’s like the dice is constantly rolling and the dice doesn’t have sides but instead whatever happens it hopes that the dice doesn’t get eaten by lions and sabretooth tigers.

Take an example as albanism. Suppose a hypothetical scenario where the species homo sapiens were competing with polar bears in antartica, and it just so seems that the ones with a white skin color camouflage better than the other, its just over generations, the one that carry the albanism gene will actually be the majority from the minority because the other homo sapiens with other skin color simply gotten chewed off from existence, never to be known again. It’s actually extremely probably that a new “group” of species to emerge due to sheer will of predation that over time and generations, the new species become too different from the original one and it becomes its own thing.

After all, imagine that some poor soul born with polydactyly—aka extra fingers or toes—just so happens to have a survival advantage.

Maybe they can climb better. Or throw spears faster. Doesn’t matter. The point is:

If that mutation helps them survive just a bit longer than the rest of us?

And they live long enough to pass it on?

That weird little bonus thumb becomes a genetic ticket to the future.

Over hundreds, thousands of generations, that once-rare trait spreads.

Then other traits pile on. Maybe better vision. Different metabolism. A slightly altered skull shape.

And suddenly... you’ve got a population that looks and acts nothing like its ancestors.

They don’t just survive—they diverge. Thus, speciation.

I went on a tangent here but its all the point to explain:

This is what it means to up their game. If you understand the nature of random genetic mutation, it’s only inevitable to have diversity in the face of adversity.

Now you understand the concept of evolution, now we can talk about convergent evolution and the shark.

Convergent evolution is when different species, from totally separate evolutionary paths, end up looking and behaving eerily similar—not because they’re related, but because the environment demanded it so that it evolves to the same solution to a problem

Let’s talk prime ocean predator build—the kind of form that shows up again and again across millions of years of evolution, like nature’s own recurring boss fight design.

We’re talking:

Torpedo-shaped body – built for speed

Dorsal and tail fin combo – stabilizer + thruster

Forward-facing mouth – direct delivery of death

Eyes on the side – wide field of vision

Streamlined everything – less drag, more bite

Now here’s the kicker: That build doesn’t come from one species line. It’s shown up multiple times, independently, across totally unrelated animals. Why? Because its simply what works. Or in other words, it is as good as it gets.

Shark (Fish)

Cartilaginous fish.

Around for 400 million years.

No nonsense. Just teeth and instinct.

OG of the apex ocean build.

Dolphin (Mammal)

Descended from land mammals.

Oldest dolphin-like fossil: 33 million years ago (Echovenator, Eocene epoch).

Developed the same hydrodynamic shape.

Breathes air, but swims like a damn missile.

Ichthyosaur (Reptile)

Reptilian, from the Mesozoic era.

Oldest known fossils: 250 million years ago (Chaohusaurus, early Triassic).

Not related to either sharks or dolphins.

Looked exactly like them.

Apex predator of its time with the same damn body build.

So what actually happened? Nature found a damn cheat code. And once it did, any creature that wanted to play in the apex predator league had to respect the meta. Didn’t matter if you were a fish, a mammal, or a dinosaur-lizard hybrid—the ocean had one rule: if you want to swim fast, hunt hard, and not get wrecked, you better show up in the same skin-tight torpedo build as everybody else. Different starting lines, sure. But everyone evolved toward the same final form. That’s convergent evolution. It’s not copying. It’s not inspiration. It’s not coincidence. It’s just physics and death pressure squeezing your DNA into a shape that works, and punishing anything that strays too far with immediate extinction.

Meet Nudibranch

Nudibranchs are a group of soft-bodied, shell-less marine mollusks—ocean floor dwellers that spend their lives crawling around reefs and rocks, munching on sponges, anemones, jellyfish, and sometimes even other nudibranchs. They’re found all over the globe and are basically the weird, colorful nomads of the seafloor. But then comes Phylliroe.

Phylliroe didn’t decide to become a fish. Its DNA got bullied into it. This isn’t some conscious glow-up—it’s the result of mutation after mutation, generation after generation, where any slug that didn’t vibe with the open ocean just got deleted from the gene pool. That’s the thing—evolution doesn’t care about your feelings. It’s just a brutal numbers game. And in the pelagic zone, if your DNA didn’t randomly spit out traits like a flatter body, some fin-like flaps, better muscle control for swimming, or invisibility mode via loss of pigmentation—you got eaten. Fast. The ones with mutations that helped? They passed those suckers on. Over time, the DNA kept stacking traits that worked. And without any central plan or purpose, the genome accidentally speedran a fish cosplay. That’s not design. That’s just natural selection hijacking a sea slug’s body like it’s modding a character in real time. So yeah—Phylliroe swims now. But not because it wanted to. Because its ancestors that didn’t? Got clapped.

Biological Edge

Every species is born into the ring with a knife duct-taped to its hand. That’s your biological edge—whatever your genes gave you that gives you a slight upper hand. Could be speed, could be venom, could be the ability to digest literal garbage and still thrive. It’s the unfair advantage nature randomly hands out and then tests under pressure. It’s what the species got to work with. And in the grand game of survival, that edge is the difference between passing on your genes or go extinct and gone forever.

The biological edge buys you time to adapt, fight, run, blend in, or out-breed everything trying to kill you. It’s not permanent, it’s not sacred, and it sure as hell isn’t enough on its own. But it’s the only ticket you get to play the game.

The Lazy Panda

Now let’s talk about the panda—arguably one of evolution’s most bizarre long-term investments. Pandas are part of Carnivora, which means their ancestors were meat-eating, bone-crushing bears. But somewhere along the evolutionary line, pandas pulled the ultimate curveball and said, “Nah, I’m going plant-based.” And not just any plant. They locked in on bamboo, which is basically green scaffolding—hard, low in nutrients, and about as satisfying as eating soggy wood. It’s so inefficient that pandas have to devour around 20 to 40 pounds (sometimes up to 80 pounds) of it every. single. day. just to survive. But here's the twist—bamboo grows fast. Like, stupid fast. Some species shoot up nearly a meter a day. So pandas found a niche with a self-replenishing food source and just posted up like lazy bastards with lifetime supply coupons.

But here’s the genius part: no one else is doing that. They found a niche where the food is abundant, fast-growing, and no one's fighting them for it. That’s their biological edge—not strength, not speed, not carnivore dominance—but picking the one buffet no one else wants to touch, then milking it for all it’s worth while sleeping 10 hours a day and occasionally rolling downhill.

Over generations, their bodies adapted—not by getting more efficient, but by doubling down. Their wrist bone morphed into a thumb just to grip bamboo better. And even though their digestive system is still built like a carnivore's (yeah, they're still running meat-eater software), they developed a gut biome full of specialized bacteria, passed down generationally, just to squeeze out some nutrients from all that cellulose. It’s not perfect. It’s painfully inefficient. But it’s the hill they chose to live on—and somehow… it worked.

Human Prisons

I had a conversation with my friend on a vacation one day, we were drinking at a really chill bar and I asked him.

Me: There’s this funny conversation that I had, and I’m curious to know your opinion, do you think that death sentence is justified or you believe that anyone whatever such crime should be rehabilitate through prison?

Him: Wow yeah that’s very hard, I guess some people really do deserve death sentence… But if you go with the free will route argument right, since we are really influenced by our environment and epigenetics, no one is really held fully accountable to their crimes because its the environment that shapes them so death sentence seems unfair.

Me: Yeah, but think of serial killers—like Ted Bundy! He escaped from prison twice and yk what he did afterwards? He started raping and killing again! It’s almost as if they can’t help himself but to rape and kill!

Him: So its a prison mistake right? The more ideal prison is supposed to be like the one at norway. I think that way a prison as a rehab center / punishment would actually make people recover

Me: Yeah, but we really need to take into account that we live in a sub ideal world where prison is already so expensive and its actually more of a lucrative business than focusing on rehabilitation. And prison nowadays man, its more likely that people who came back from prison would actually be more violent and uncivilized instead of being cured.

Him: So what’s the solution?

Me: I’ve been thinking about this right, if we take focus from the purpose of a prison, is that to detain people who couldn’t behave in the set civilization, and prison as a system is meant to make inmates come out of a prison to understand why rules are made to be obeyed and they must behave in accordance to the rules set by the civilization right. Hear me out it’s going to sound really crazy. We metaphorically will travel back in time.

Him: laughs. What do you mean by travelling back in time? How the fuck do you travel back in time?

Me: No no no, Suppose that we are able to make an environment that is similiar to pre civilization, like how early homo sapiens survive on their own. I’ve been thinking about this right, we as humans actually have very little probability to survive in the wild, yet here we are drinking with a glass molten miles away from here with a wine brewed miles away from here. But with this great reward from civilization, it must start small somewhere, and it starts by obeying rules set by the small tribe. In order to be able to get containerized wine bottle, there’s earlier problem to be solve and that is to eat every day from hunting animals, and there are rules to it. There are rules for cooperation, to ration your food among the people who helped hunting, to not steal, to not kill, to not rape, these very simple rules that somehow some maniacs and serial killer doesn’t seem to understand unless they learn from experience.

Me: It’s like putting them on a pedal of the civilization in terms of small tribe first. They need to understand through experience “Why it sucks when someone doesn’t obey the rules that they have state as a tribe/civilization.” If a civilization say USA, put inmates like this, its the same as saying “If you don’t like our civilization, then try go make your own civilization.”

As the human species, its a fact that we’ve done it, we survived in the wild. Full of foxes, lions, sabretooth tiger, vipers, gorillas, ape, macau, etc etc. What was our biological edge over these ever species that compete with us for the same resources?

What was the driving force of evolution that able to make us the prime predator?

It was not dorsal fins, not fangs, not even spring like legs, not the ability to climb trees with agility, not sharper eyes, not even god-like reflexes. It’s social coherence.

We built the alphabets from poorly written drawings. We made the letter “A” from a poorly drawn ox head.

We strived out of the premise of “Please understand me and I’ll try my best to understand you so we can survive.” Cooperation out of social coherence is the actual blood and bones of our species. It is based on trust and mutual understanding of contexts.

If we want to outlive the wilderness in the savannah, we need to understand a lot of contexts as it comes to foraging, killing animals, shelter from rain, and not break the trust that our little tribe has formed, not to kill other people and not to rape other people. We probably don’t learn this just by telling other people what not to do, but the emotional impact that hits us when it happens. That’s why emotional pain inflicted by us grows as trauma, its almost as if we want to kill the person, give them what they deserve, the pain that we relive in our dreams, as a method of the brain to remember whats important to us. Context that lives not only from verbal understanding, but smeared and painted by strong emotions. It has become so important to us that up to this point we are the most emotional species out of all species.

Context with great depth of emotional layering, the most suicidal species on earth, the most prone to murder species on earth, the most wanting to be understood species, the most emotionally troubled out of all, the one that can write and convince other people to commit suicide or give 10 bananas in exchange of paper.

Context follows a simple rule, it needs a 3D space across time.

This context building is what makes us able to hunt in groups by learning what it means to fast for a day due to failure in hunting session or even have a brother get chewed up by lions.

Help us to cooperate to make shelter from the rain and knowing how it feels to lose a brother from hypothermia or be stuck on a windy thunderstorm.

Help us to fairly rationed our hunted meat to the people we care and to understand how it feels to be given unfair ration of our hunted meat.

Dopamine is greatly present in our brain and has shown that what to do, what not to do, what to anticipate when doing something that potentially rewarding is actually regulated on our neurochemistry.

Dopamine didn’t just tell the us what felt good. It told us what to chase. It whispered, “Fire = warmth. Meat = good. That berry bush = jackpot.” It wasn’t just reward—it was anticipation. A neurochemical breadcrumb trail saying "Walk that way, greatness might be there." Every time a hunting party returned with fresh kill, dopamine wasn’t just the celebration—it was what got them up at dawn the next day to try again. No map, no guarantees—just the dopamine-fueled idea that "maybe this time, we’ll eat."

No caveman survived alone. Try hunting a by yourself—high likely you’d get butchered. You needed someone to watch your back when you slept, someone to scream “RUN!” when the saber-tooth came crashing through the brush, someone to pick the ticks off your scalp while you roasted lizard over the fire. That’s where oxytocin came in. It wasn’t just love—it was biochemical loyalty. Every time you shared meat, locked eyes in a silent “we’re still alive,” or wailed together when a hunter didn’t return—oxytocin carved a bond in your nervous system.

Norepinephrine is what lit your neurons on fire when the bushes rustled wrong. When a shadow flickered at the edge of the torchlight, it funneled all your blood to your legs, narrowed your vision, slowed time itself so your spear could fly true. This is what seared the lion’s roar into your soul. What made your muscles shake after the danger passed. Your body’s internal air raid siren saying, “Remember this, or die next time.”

We rely on understanding and predicting context to survive, it is wired in our brains to the point that we can’t help but mixing perception with prediction, it is both our greatest edge in existence and our greatest demise. Life flourish and is taken away voluntarily from this tweak.

Before exploring further, I must explain the concept of “Symptoms from one’s Biological Edge”

Symptoms from Biological Edge

Biological edge is previously defined as something of a feature that a species has that actually helps giving the species an upper ground against their competition competing on a shared resources.

A Symptom from Biological Edge is a non-essential emergent trait that arises from an evolutionary adaptation. It wasn’t selected for directly, but emerged as a side effect of a trait that was. Over time, these symptoms may gain cultural, emotional, or psychological importance—despite not being necessary for survival or reproduction.

Elephant’s Solidarity

This is a picture of a calf elephant attacked by lions.

This is a picture of a lion hesitating to attack the herd of elephants.

The majestic lion is unbelievably thinking twice to strike his target, a rare sight to behold. Elephant’s oldest fossil is found to date back accross 60 million years ago. While some species can survive travelling on their own but elephant would need to continously form the “Phalanx Formation” where it stands side by side making an formidable wall that is even worthy of fearing by the literal fucking apex predator.

The elephant doesn’t make compromises, it doesn’t sacrifice one of their kind so another benefits from the act. It doesn’t say,

“Tough luck, kid. You were the smaller one.”

It says,

“You’re one of us. If one falls, we all drag the corpse or die trying.”

It forms a dead-strong phalanx shield to protect each of their own from predator ambush.

Why?

Because the price of not protecting one another is far more expensive than bruises and broken bones.

The price… is grief.

The kind of grief that doesn't just pass. The kind that etches itself into memory. The kind that makes the matriarch stop mid-migration to stare at the sun-bleached skull of the calf she couldn’t save two dry seasons ago.

You want to understand the cost of a broken bond in a species wired for social coherence? Watch an elephant linger at a graveyard made of bones. Watch it wrap its trunk around what’s left and just stand there. Silent. Immovable.

They fall into depression. They starve themselves. They withdraw from the herd. They become quiet—not because they’re safe, but because they’re hurting. They don’t run. They grieve. And grief, my friend, is not a survival skill. You can’t eat it. You can’t fuck it. It’s not adaptive. It’s residue. Leftover soul-gunk from the same neural circuits that gave them community in the first place. That’s the biological bill. You evolve connection strong enough to build a matriarchal dynasty—and now you carry your dead with you. Not just their bones. But the absence of them.

That’s the cost of bonding in a species that remembers. You get grief as your receipt for love. You get silence and starvation as your inheritance for connection. It’s noble. It’s beautiful. It’s exhausting.

And so that’s why the phalanx exists. It’s not just for defense, not just for strength in numbers, but because the cost of letting one fall behind is simply too high. Because they know—whatever “know” means in the language of species that do not write books or build statues—that losing someone changes everything.

But nature doesn’t always roll this way. Some creatures dodge the grief bill entirely. Not because they’ve transcended it. But because they never picked up the tab in the first place.

Meet the Nazca Booby

Now the Nazca Booby does not build a phalanx. It does not mourn. It does not remember. It does not pause beside the bones of its lost family member. This is a bird that lays two eggs not because it wants two children, but because it doesn’t trust the first one to hatch properly. It’s a backup. A spare. A contigency plan.

Now when both eggs hatch, the older chick will immediately look at its sibling and realize that there’s not enough food for both and probably say “You’re not HIM bro...” And without skipping a beat, without needing to think or weigh the consequences, it will proceed to attack its sibling. Repeatedly. Until the weaker dies.

And the parent? The parent doesn’t intervene. Not even a little bit. There is no maternal shriek of protest. No grief. No awareness of loss. That’s the thing. The Nazca Booby doesn’t carry the absence. There is no emotional aftermath. No hollow space left in the nest, no moment of pause to wonder what might have been.

And yet, both the elephant and the Nazca Booby have survived. Both have passed the test of natural selection. One through connection and memory and cooperation. The other through absolute zero empathy and ruthless elimination of the weak.

There’s even a well documented with 4K visuals on this happening produced by Nat Geo,

The silver lining is, would you rather be the elephant or the Nazca Booby?

It seems to me that Nature has put us to a position that we didn’t even have the voting rights in the place and we somehow ended up in a good place (if your answer is the same as mine and that is the Elephant.)

“Keep Trying Until its as Good as it Gets”

Every animal that currently exists, has a role that they fill on their ecosystem.

He does not need to be perfect, he only needs to be as good as it gets for the ecosystem, which in return, makes him look as if he’s perfect. It makes sense because its only either that or extinction. When it comes to extinction, the one that competes with you for the same amount of resources will always try to out-edge you. You have no choice but to out-edge them on their own and hope the genetic lottery and time are kind enough.

You might initially think nature has a poetic side. You might want to believe grief is profound and beautiful, like some Shakespearean monologue of the soul. Which is good (I think maybe), because life is so bland without its romanticization, might as well romanticize life and all it contains while we live right?

Though, if you try to see things without the curtains of romanticization, you might see a whole different dark beast. In which I think I would call as “The Beast of Absurdity." It’s absurd because it’s almost as absurd as thinking why the elephant deserves see its mother die and mourn for decades to come, and thinking what the weaker nazca booby did to deserve such gruesome death? It’s because those answer does not require an answer because evolution does not need to justify itself. Evolution is good at doing what it does regardless if it makes a baby kills another baby inside their mothers womb (a lot of animal does this), or infect the brain of a living bain and eats it inside out to release spore out of the lifeless corpse to continue reproducing its genes, it is also the same force that is responsible that made hyenas shed tears when they found out that their baby is gone from the nest after her hunting session.

In a lesser word, nature's just a drunk scriptwriter throwing darts at a wall labeled “What Works.” Between all love and murder, evolution cares only one thing, and that is to survive beyond all means, and it shows.

Penguins that Loved

These guys are... weirdly romantic. Like, too romantic for something that screams like a broken saxophone and waddles like its shoes are too big. But it works. Somehow. Because what they’re wired to do isn’t chase as many mates as possible like a horny frat dolphin, no. These little tuxedo fellas are on that one soulmate timeline.

They pick a mate. One. And that’s it. That’s the penguin. That’s their penguin. They don’t swipe left. They don’t say “you’ve changed.” They pick one and build their whole icy soap opera around that one penguin for life. And how do they show their love? With rocks. Literal rocks.

The male brings pebbles and starts stacking them like a broke penguin architect trying to impress his girl with a pile of driveway gravel. And it works. She sees the stack and goes,

“Alright. Yeah. You’re him.”

Then every year, after migrations, storms, and the kind of weather that kills you if you blink wrong—THEY COME BACK. To the same place. For the same penguin. No GPS. And somehow—somehow—they find each other again. Touch beaks. Scream a little. Go, “We’re alive. Let’s do it again.”

I always believe that when it comes to a “partner” there’s need to be a “stress test.” I always doubt when people say that he/she has never gotten into a fight with their partner, like the saying “if its too good to be true, then it probably is.” And what better stress test than living in the antartic fucking winter. We’re talking a condition so fucking bad that even your food is still swimming and 50 miles away under a frozen ceiling, the wind is throwing strays at you at 80 km/h like it’s got beef with your entire bloodline, and the sun? Yeah, it clocked out for the season. Just dipped. Gone for months. Everything out there wants you dead—including the silence.

So yeah, if a penguin can survive that with someone, year after year, and still come back and scream at them like “AYYY you made it!”—then maybe that’s what soulmates are. Not some rom-com fairytale, but just “we didn’t die and I still kinda like you.”

Not to mention that IF you have a kid that is still in egg form, if it touches the ground for longer than 12 seconds it basically becomes a popsicle.

That kind of pressure doesn’t leave much room for experimentation. Which is maybe why they commit so hard. Not because they’re romantic in the human way. But because there’s literally no margin for error.

There’s something oddly beautiful about how committed these penguins are. Like, really think about it—every year, after vanishing into the cold for months, they come back. Not just anywhere. Not to just anyone. But to that one. That same awkward, screaming bird from last season.

They don’t forget.

They don’t start over.

They return.

There’s a kind of romance in that. Not the rose-petals-on-the-bed kind. Not the grand gesture or the candlelit nonsense. But the kind that shows up. Again and again. Even when the sky is trying to kill you and your bones feel like glass.

But in a world where the individual is molded by the environment, and how two birds (between penguins and nazca booby), how can one so different from the other? Why cant everyone just love? Then, I’m once again faced by the beast absurdity that is not obliged to give me any justified reasons why things the way they are for certain and beautiful meaning. But it does left breadcrumbs.

What if the reason they stay with one partner is because the world they live in is too brutal to risk anything else? Because in that kind of place—where one wrong move means your only egg is gone forever—there’s just no space for trial and error. No space for “finding yourself” or “just seeing where it goes.”

And somehow, that’s what makes it romantic. Not in spite of the cold—but because of it.

Like, “I could die out here. But I’d rather freeze with you than figure this out with someone new.” That kind of love. Sharp-edged. No backup plan. Just two idiots and a rock nest against the wind.

And yeah, maybe that’s not what we think of when we say “love.” But maybe it’s the only kind that actually lasts.

It lasts…. Oh brother it sure does lasts….

Grief as the symptom of love

For this section, I’ll open a snippet from a documentary and narrate bits by bits so watching is optional

Is there such a thing as insanity among penguins?

I try to avoid using the terms "insanity" or "derangement." I don't mean that a penguin might believe he or she is Lenin or Napoleon Bonaparte. But they just go crazy because they've had enough of their colony.

Well, I’ve never seen a penguin bash its head against a rock... but they do get disoriented. They end up in places they shouldn’t be, a long way from the ocean.

These penguins are all heading to the open water to the right.

But one of them caught our eye — the one in the center. He would neither go towards the feeding grounds at the edge of the ice nor return to the colony.

Shortly afterward, we saw him heading straight towards the mountains, some 70 kilometers away.

Dr. Ainley explained that even if he were caught and brought back to the colony, he would immediately head right back toward the mountains.

The rules for the humans are: do not disturb or hold up the penguin. Stand still, and let him go on his way.

And here he is, heading off into the interior of the vast continent.

With 5,000 kilometers ahead of him, he’s heading toward certain death.

At this point I am not very sure that I need to reiterate the point on how species that are ABLE to love, grief will manifest, it will simply manifest.

It’s almost as if saying it’s either you become a soulless nazca booby, or capable of loving but it shows an inevitable emergent property that allows grief as the anti-matter. Thus, grief is a symptom of love.

And I think it’s beautiful. Not only because they and us couldn’t have it any other way. But also because after we observed all of this, we wouldn’t want to have it any other way.

It’s actually as good as it gets. Cause if they are not the way they are and if we are not the way we are, we will simply die out of extinction.

Nothing less, nothing more.

Just enough.

Something of Importance

A bacteria may kill itself.

It does so when it gets infected by a virus.

If it doesn’t kill itself, its “body” will be a host for the virus to replicate itself and eventually forces the bacteria to explode, spreading the virus to neighboring cells.

The question that I have is, why does it care so much?

Why does something so small care about something so big?

The virus also, why does it seem to care to spread its genetic copy?

Why does something so small care about something so big? Something that is 5000 years away.

What “it” knows is that, if it doesn’t do that, its genetic code will be simply lost. It dies off. It’ll never continue, it’ll never see its kind or itself again, even if they are not able to see, it still wants to multiply and spend all means necessary to make sure its genetic code gets passed down.

Why does it seem to care to an extent it’s worth killing itself for?

A chemist would say, because it’s chemically inevitable, it’s just chemical reactions, you cant put salt and water on a flask and not expect it to react. It will most certainly will react, it is bound to react, it is bound to happen. Because because this is positively charged and that is negatively charged, it’s only natural for it to react.

I want you to chew the fact that all the bacteria does or will do is based on this very simple premise, it eats, it stopped eating (sleep phase), it moves, to eventually fuel energy for it to do replication or divide itself into two maintaining identical copy of itself.

I couldn’t seem to find a reason why does it seem to bother so much. It is certainly not happy, its judgement about the world is limited to its perception of the world. It does not get rewarded, there doesn’t seem to have a reason why it kill itself to protect others, it’s a fucking bacteria.

Will you kill yourself if you were infected by a supposedly deadly virus as a means to stop it spread to those around you?

It is not rewarded by anything but yet it does it.

Complex neural circuitry that can trace reward and motivation feedback loop only happens later in more complex creatures, but it seems to me, the very same concept was already long ago even without the heightened perception of “what it means to care.”

It spawned into existence, everything that it does and will do is to sustain the high probability that it can succeed with its mission. It simply can’t help itself to not kill itself when push comes to shove with its mission.

It’s an “inevitable chemical reactions” based on the circumstances and environment provided by the arrival of a virus.

“How much of it is new?”

I am not sure how to feel after knowing that there’s a part of the brain that modulates what feels “real”.

There are people out there who watch the news and could feel for maximum certainty that the news anchor are talking about him, plotting against him, planning to kill him even.

Hearing voices that are not there, and believing some things that are not supposed to be believed.

How much of “these” are actually not just some “inevitable chemical reactions?”

I saw the sunset and smiled

I fell in love as if it’s the only thing I can do in “certain situations”.

I see her smile and I could brazenly say that she is the only thing that I care about the world.

I smoked fentanyl and then I died.

I can feel with outmost certainty that I died.

I spontaneously exist.

I don’t know why I care, though, I feel that there’s nothing else for me to do than to care, everything else is just symptom of me caring.

If I were to be punished to move a boulder up a mountain for eternity. I might as well pretend that I care about moving it up, because I have no other choice, I might as well care.

In the face of such absurdity, where nothing is in your control, the only thing that is in your control is your attitude.

I could imagine that even a bacteria is as confused as we are to spontaneously exist and need to move its flagella. Even worse is that it doesn’t come with a hedonistic reward function, it just does it thing because it’s the only thing it knows what to do.

Everything else that it does, is a symptom of one crucial fundamental act, convert external resources into energy to keep living until it passes on its genes.

So why does something so small care about something so big?

Maybe because caring—even when it hurts—is how life keeps happening.

Chemical Reactions under the Heroic Curtain of Self Sacrifice

So let’s go back to our dear bacteria, shall we?

It doesn’t think. It doesn’t feel. It doesn’t even try. But somehow, it wiggles around, eats, divides, and occasionally done something “noble” like killing itself if it means to save others.

But it’s not doing any of that on purpose.

In other words, it couldn’t help itself but to commit suicide when faced in such absurdities of getting rawdogged by a bacteriophaged virus

It’s called programmed cell death.

No soul. No Shakespearean monologue. Just molecules tripping over one another and hitting the self-destruct button.

Here’s how it works, simplified:

MazE is the antitoxin.

MazF is the toxin—an mRNA cleaving enzyme that halts all protein production and basically nukes the cell from the inside.

Under normal chill conditions, MazE keeps MazF in check. But when the bacteria gets stressed—like, say, it's invaded by a bacteriophage (a virus for bacteria)—MazE degrades faster than MazF.

And when MazF is left unsupervised?

It goes feral.

Starts chopping up all the mRNA in sight.

Translation stops.

Cell functions collapse.

The bacteria dies.

Not out of courage.

Not out of empathy.

But because the chemical balance tipped, and a molecular tripwire got triggered.

So no, the bacteria doesn’t choose martyrdom. It doesn’t cry little protein tears for its bacterial brothers. What happens is this:

The antitoxin holding the toxin at gunpoint just got digested faster than expected. And once that leash snaps, the toxin loses its goddamn mind. It slashes through mRNA like there’s no tomorrow (there isn’t)—and boom. Everything stops. The cell collapses like a stressed-out intern that just saw their Slack ping.

The “heroic sacrifice” is just the result of molecules reacting faster than they can be unreacted.

It’s as inevitable as mixing baking soda with vinegar, tossing mentos into a coke bottle. You align molecules a certain way, atoms bumping into each other, finding stability, and accidentally forming something that started metabolizing before it knew what metabolizing was.

“I” Keep Living

Bacteria “understands” the importance of preserving legacy more than we understand why need to invest in index funds without it needing to understand the concept of space-time and its implied consequences of keeping its heritage alive and well. Even if it is implied indirectly.

That chemically-triggered meltdown? That bacterial cell lighting itself on fire because a virus walked in? Turns out, it’s effective.

Why?

Because the bacteriophage, the virus that just crash-landed inside the cell, needs the host machinery to replicate. It hijacks the ribosomes, the polymerases, the whole protein production factory, to start making virus babies like it’s running a biotech startup.

But guess what happens when the host cell yeets itself before the virus can finish?

The virus dies with it.

No replication.

No viral spread.

Just one dead virus, trapped in a biological suicide note.

So even though this bacterial cell dies, its neighbors are safe. The virus didn’t get a chance to turn the whole block into a viral frat house.

From an evolutionary perspective?

This is the ultimate uno reverse.

The trait gets passed on not because the individual survived—but because the population did. Bacteria that randomly evolved these self-nuking systems stuck around longer. They outcompeted the ones that let viruses turn them into goo factories. And over generations, the genes for toxin-antitoxin systems got baked into the code like emergency grenades.

So what looks like “self-sacrifice”...

What smells like “honor”...

What sings like “do it for the greater good”...

Was just chemical warfare, so effective that evolution said,

“Yeah... let’s keep that glitch. Run it again.”

Keep in mind that evolution is a label that is defining a process. A process that took generations to observe.

The bacteria as an individual, does not have a say on this, it does because it can’t help itself but to do it. To kill itself when the time has come. As certain as if you throw a baseball up to the sky, it will certainly fall back down. As certain as if you hold your hand on an exposed electrical wire, you will get electrocuted.

Symptoms from a Biological Edge: The Bacteria's Curtain Call

This—this molecular freakout disguised as valor—is a textbook Symptom from a Biological Edge.

The biological edge here is the ability to stop a virus from spreading. Not by building walls. Not by deploying an immune system with memory and antibodies. Nah. That’s future-people stuff.

This is preposterously primitive, primal-level defense. A failsafe.

The symptom? It just so happens to look like a noble sacrifice.

It’s not “I die for you, my kin.”

It’s “The chemical reaction hit its limit, and now my internal kill-switch just kicked in.”

But to the outside observer? To the story-loving, symbolism-craving species reading this right now?

It feels profound.

It feels selfless.

It looks like a moral decision.

We—humans, observers, storytellers—can’t help but romanticize the pattern.

We call it courage.

We call it love.

We call it "doing the right thing."

But to the bacterium? There was no script. No dilemma.

Just MazE broke down faster than MazF.

Just a timer went off.

Just inevitability.

And yet—somehow—that cold mechanical twitch saved lives.

It protected the colony.

It bought time for others to reproduce.

It passed on the gene.

And here’s where it gets really philosophical:

What if that’s how everything starts?

What if love, loyalty, grief, heroism—all of it—is just the long tail of traits like this? Traits that began as raw chemical advantages. Traits that got selected again and again, until eventually... one day... a species like us looked at a bacteria and said,

“Damn. That’s kind of beautiful.”

That’s the weird thing about emergent properties.

They don’t start with intention.

They start with math.

They start with the math that works.

And then, over generations of pressure and pattern, they start to look like poetry.

The Energy to Fuel Tears

Bacteria needs energy to survive, eat, and kill itself, and it doesn’t do it ever so freely. It costs something and its something that it “learns” by taking molecules from outside itself, and “synthesize” it to become something of a currency to fuel itself to do all acts it can do.

So how does a bacteria make that energy?

Imagine the bacteria grabs some raw material—like sugar or whatever chemical trash is floating around—and throws it into a tiny internal factory. That factory’s job? Break it down. Strip it. Squeeze every usable drop of energy out of it.

This isn’t magic. It’s more like a biological recycling loop. You feed in the leftovers of molecules, and what comes out is power—a kind of molecular cash called ATP.

And the way it gets there?

That little loop?

That engine under the hood?

That’s the Krebs Cycle.

It's a universal trick of nature. Bacteria use it. Plants use it. Elephants use it. You used it just now to blink your eyes and scroll your phone.

The Krebs Cycle is like life’s version of a power strip: it takes fuel and turns it into plug-ready energy. Efficient, repeatable, and everywhere. It’s so reliable that evolution just… never changed it. If you’re alive and breathing oxygen, this cycle is probably grinding inside your cells right now—quietly buying you another second of being alive.

What it gives isn’t just energy—it gives permission.

Permission for the cell to move. To grow. To think.

Or in some cases... to kill itself.

Because even suicide isn’t free in the microscopic world.

Even dying with dignity comes with a metabolic bill.

And that bill is paid, every time, in ATP.

It’s one thing to know that all life sustain itself by consuming resources available to it and converts it into energy packages to sustain all activities it wishes. But its a whole another beast to appreciate the fact that the krebs cycle appears in all living forms as a way to convert the resources consumed to become energy.

From Molecules to Memory: When the Symptom Learns to Feel

If a bacteria can mimic sacrifice—if a sack of molecules without eyes, without a brain, without a single serotonin receptor can perform an act that looks like heroism—then what does that say about the elephant?

The one who pauses mid-migration.

The one who wraps its trunk around a sun-bleached skull and just... stands there.

Or the penguin who fights frostbite and starvation just to scream beside the same penguin it screamed with last winter?

Because here’s the thing—

That bacterial suicide? It never “meant” anything.

But it worked.

It protected others.

And because it worked, it stuck.

It got passed down.

And somewhere, millions of years and trillions of cells later, it became a nervous system. Then a brain. Then a memory. Then a feeling.

And now?

Now it hurts when someone dies.

Now we remember who we lost.

Now we carry grief in our bones like elephants,

or cling to soulmates like penguins in tuxedo bodybags.

All because somewhere down the line, the math of sacrifice got selected.

And then, eventually, the symptom started to feel like a choice.

That’s what grief is, isn’t it?

Not adaptive. Not useful. Not helping you eat or fuck or run faster.

But residue—the shadow cast by a brain evolved for bonding.

By chemicals originally tuned for survival.

Hijacked. Twisted. Romanticized.

You lose someone, and your whole internal chemistry collapses like a bad economy. You’re not just sad. You’re metabolically shattered. Eating hurts. Sleep is a joke. Dopamine goes missing. Oxytocin sulks in the corner. Norepinephrine has the audacity to keep you alert when the threat is already gone.

And it makes you wonder:

Are we still just running ancient programs?

Is all this grief—the pain, the loyalty, the love—just a Krebs Cycle of emotion, looping endlessly because the early version happened to keep the tribe alive? Just because the bacteria that sacrificed itself prevents the other bacterias to not be murdered by the viruses?

Murder as the Inevitable Natural Order

From virus killing bacteria to humans killing the wooly mammoth

From necessary killing—for survival,

to unnecessary killing—just because we could,

and even further—to kill something that is simply “not like us.”

If you rewind the tape back to early Homo sapiens—raw, barefoot, sunburned, starving—we didn’t have many options.

You couldn’t just live off grapes and leaves and hope to make it through the Ice Age.

You needed meat.

Protein.

Something dense enough to rebuild your muscles after chasing a gazelle for eight hours and still missing.

So we got better at killing.

Sharpened sticks. Sharpened bones. Sharpened stones.

We didn’t just kill animals—we became really, really good at it.

We started understanding where to stab, when to strike, how to trap. Then, we can kill for the sake of killing.

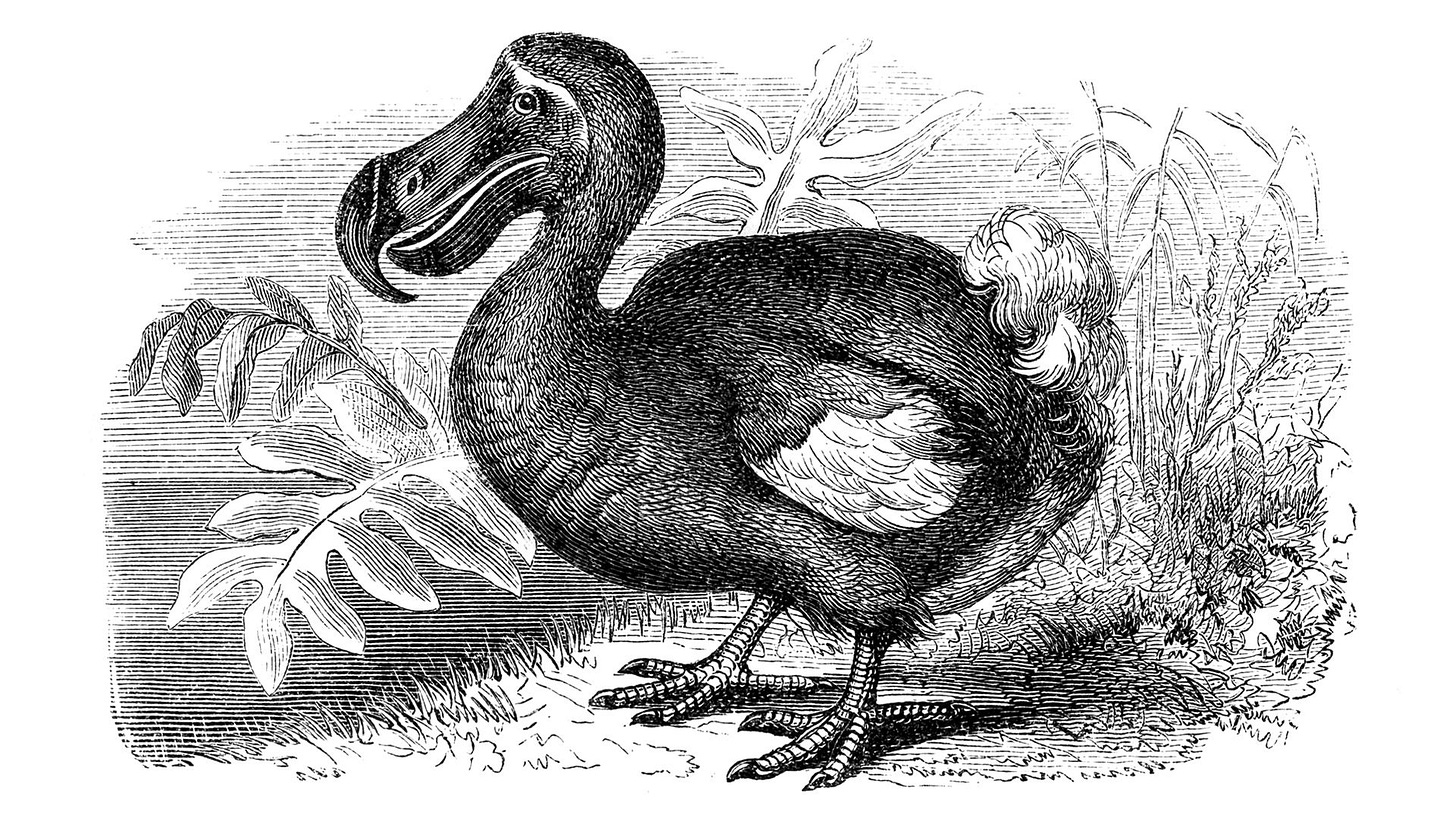

Enter the Dodo.

A bird so peaceful it forgot how to fly.

Lived on the island of Mauritius with zero predators for thousands of years.

Didn’t need fight or flight—just chill, forage, nap, mate, repeat.

The kind of animal that evolved under the assumption that the world was kind.

Then we showed up.

You’d think we killed them because we were starving.

Nope.

Some Spanish explorers were documented clubbing dodos to death—not to eat—but to use as firewood.

Let that sink in.

Not meat.

Firewood.

We burned birds because they were big, stupid, slow, and conveniently flammable.

We treated them like wet logs with feathers.

Why?

Because we could.

Because they didn’t run.

Because they didn’t bite back.

Because they didn’t fit the world we were building.

And within less than a century of meeting us:

Extinct.

Gone.

Forever.

Not because of a grand event.

But because we didn’t even think twice.

The Tasmanian Tiger

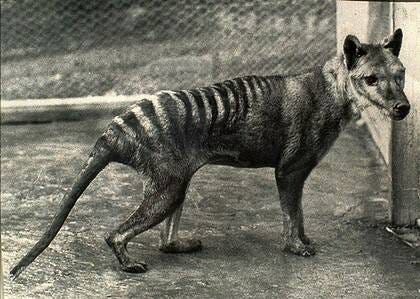

It’s not really a tiger. It’s not even a feline. It’s a marsupial that looked like a dog, moved like a big cat, and had a pouch like a kangaroo. It was nature’s sketchpad on shuffle—an evolutionary remix that, to our settler eyes, looked too weird to trust.

We looked at this ancient, niche-filling organism and said:

“That thing’s eating my sheep. Kill it.”

Governments offered cash payouts for every Tasmanian Tiger carcass turned in. Hunters lined up. Farmers shot on sight. Museums started collecting “last specimens” while the animal was still technically alive—because even science had given up early.

And just like that, in less than a century, we deleted an apex predator that had held its ecosystem in balance for millennia.

You see, the Tasmanian Tiger wasn’t just vibing alone in the wilderness. It was part of a larger system—a top-down regulator in a delicately-tuned ecological orchestra.

Take it out, and suddenly herbivores start thriving. Not in the cute way. In the unchecked population boom, lawnmower-with-legs kind of way. Kangaroos, wallabies, wombats—creatures that once had to keep their heads down and be wary, suddenly walked like they owned the place.

Because guess what?

They did now.

Without the Thylacine, they ate more. They bred faster. Their populations swelled like a bad algorithm left running overnight. And all those grazers? They didn’t just nibble politely. They decimated the underbrush.

They turned Tasmania’s lush grasslands into short-cropped, dry stubble. All the moisture-retaining vegetation? Gone. What’s left?

Kindling.

So now you’ve got dry grasslands under an Australian sun, with more feet trampling through them, and fewer predators to keep the herbivore hordes in check.

And when the lightning comes?

Wildfires.

We didn’t just kill the Tasmanian Tiger.

We killed fire prevention.

We killed ecological balance.

And for what?

A few sheep?

Here’s the kicker: even if the Thylacine was snacking on a lamb chop every now and then—so what?

That’s what apex predators do.

They cull. They stabilize. They don’t overkill, they balance. They are the violent accountants of the natural world, making sure no one species gets too cocky with the biomass. You let the herbivores party too hard, and suddenly your grasslands are napalm waiting to happen.

But we couldn’t see the math.

We saw a monster. A pest.

Fear of Death that Drives Learning

Long before cities, long before borders, long before people could even spell “civilization,” the earth was soaked with blood. And we’re not just guessing this based on folklore or artistic murals of spearmen. We know this because of what we’ve found buried in the dirt.

Scientists started noticing something strange in our DNA—a massive genetic bottleneck that affected only men. Specifically, the Y chromosome diversity plummeted a few thousand years ago. In simpler terms, almost all male lineages vanished. Like, 95% gone. The numbers are absurd: for every 20 men alive before, only one of those lineages survived. The rest? Wiped from history. Erased. Like they never existed.

You’d expect a natural disaster, right? Maybe a plague, or a flood, or a volcanic eruption? But that’s not what happened. If nature were responsible, the damage would’ve been more evenly spread—both men and women would have suffered. But the mitochondrial DNA passed down through women? Barely touched.

This wasn’t a flood. This was a war.

And we know this, not just from our genes—but from what was left behind.

Archaeologists have uncovered over 250 late-Neolithic sites in Europe alone, filled with human remains that tell stories far more graphic than any textbook. Skulls split clean in half, then hollowed out and used as bowls. Mass graves filled with men and children—but not women—suggesting the women were taken as spoils, or trophies. Some skeletons were missing hands, arms, legs. Some were dismembered, others defleshed, some even roasted. In one infamous site in Herxheim, Germany, they found over a thousand individuals, from babies to elders, all processed like cattle—tongues removed, bones cracked for marrow, and skulls stacked.

Imagine being a traveler back then. You wander too close to the wrong settlement. You’re captured, tortured, eaten, turned into a warning sign for the next unlucky soul. It’s not myth. It’s literal. It’s evidenced in carbon, trauma lesions, and bite marks.

And you start to wonder—what happened to the people who didn’t see that coming?

The ones who didn’t fear what might happen?

They were the ones who got turned into soup bowls.

This wasn’t just survival of the strongest. It was survival of the most alert. The most aware. The ones who learned to connect dots, even paranoid ones. Because those dots were real.

Those who survived weren’t the ones who charged into battle with brute strength. They were the ones who watched patterns, who feared betrayal, who predicted danger before it arrived. Those who didn’t learn fast enough weren’t just punished—they were erased from existence.

That’s the consequence of failing to fear what might happen.

And fear—true, predictive fear—isn’t the same as running from a bear. That’s instinct. It’s basic input-output reaction: see threat, flee. But to look at a friendly tribe and say, “They’re smiling a little too much,” or “They’ve visited twice this week without reason”—that’s contextual fear. That’s learning. That’s what evolution favored.

The world didn’t just select for survival. It selected for forecasting. For contextual awareness. For the ability to remember that last season, the people who didn’t put up walls vanished. That a gathering of clouds and silence in the trees meant something bad was coming. That seeing too many crows was probably not good.

Fear became the driver of context. And context became the foundation of cognition.

The leap wasn’t physical—it was neurological.

The Rise of the Anxious Killer

The Neanderthals were walking tanks

Thick bones. Massive muscles. Barrel chests. Eyebrow ridges like storm awnings. If you squared up with one in a fistfight, congratulations—your skeleton became a museum piece. They were built for pain. Built for ice. Built for the kind of world where predators had fangs, winters could kill you faster than starvation, and meat didn’t come gift-wrapped in packaging—it came with tusks. But for all their strength, they lost. And we won. Not because we were stronger. But because we were scared.

Homo sapiens were smaller, skinnier, softer. But we were smarter. Not in the sense of algebra or philosophical monologues—smart in the way a raccoon is smart. In the way an anxious person is smart. We didn’t charge. We observed. We noticed that when you throw a spear instead of stabbing it, you don’t have to get near the thing that wants to murder you back. We learned distance. We learned to predict. We developed ranged weapons—spears with throwing power, atlatls, eventually even bows. We figured out how to kill while standing way over there.

How do we know? We have the receipts. Neanderthal remains have been found with trauma wounds that match the kind of damage seen on prey—deer, reindeer, bison—that were hunted by Homo sapiens. Same cut marks. Same slicing angles. Same technique. Neanderthals were found with a rib puncture wound so precise, researchers believe it came from a high-velocity projectile—something Neanderthals didn’t use. But we did. The implication? That dude was hunted like a deer.

Even worse, a Neanderthal jawbone was discovered with slicing marks—nearly identical to butchered animal carcasses. Now, we can’t prove the guy was eaten. But the marks are clean, deliberate, and eerily familiar. Either we ate him, or we dismembered him as a trophy. Either way—he didn’t die peacefully.

We didn’t just throw spears. We redefined danger. Neanderthals had to be close to kill. We could do it from distance. It’s the birth of asymmetrical warfare—setting traps, ambushing, killing from distance.

So here’s the truth: the species with brute strength lost to the species with predictive fear. The species that could throw a rock further than it could scream. The species that hid behind trees, peeked through leaves, calculated angles. That’s us.

Neanderthals lived in the present. We lived in the future.

And that—right there—is the tipping point.

We started connecting events not just by reaction, but by context. That’s the key difference. You kill a mammoth? The Neanderthal celebrates. You kill a mammoth? The Homo sapien asks: “Did the others see us? Will they come for revenge? Is this migration pattern predictable? Can we corner them next time?” We didn’t just win the fight. We started plotting the next one.

The world began rewarding the paranoid. The cautious. The ones who noticed that when birds go silent, something’s coming. The ones who realized the way a deer twitches its ears before bolting. The ones who paid attention, because not paying attention meant extinction.

This wasn’t just survival of the fittest—it was survival of the most context-aware.

Fear wasn’t a weakness. It was a compass. It taught us that trauma could be useful. That memory could be weaponized. That patterns weren’t coincidences—they were warnings.

So while the Neanderthals swung clubs, we whispered stories. We passed on knowledge. We taught our kids not just to run—but why to run. Where to hide. How to guess. How to learn.

That’s the real edge. That’s why the bones of Homo sapiens became the foundation of the future, and Neanderthal bones became archaeology exhibits.

Fear of Something Bigger than Ourselves

Our fear used to be more tangible, from bushes near our hut is a certain possibility of death from lions, to the fear of not having enough money to pay next month’s mortage, or student loan debts, unemployment, failing technical interviews, being broke for the next x years, etc etc.

I've thought to myself that it is only natural for people to believe something greater than themselves. It is somehow symetrical to the hostility of the environment/situation towards the individual. There are instances where our situation and our place in the universe renders us powerless to our circumstances. At this point we are left with either hope that things will go better or giving up. Hoping alone is not enough, we crave for signs that our prayers are answered, this results in self-reinforcing belief system that we would eventually take any sings by means that we are the hero in the universe in an otherwise cold and uncaring universe.

Quality of life has significantly increased across millenias undeniably, the ones that are denying this are either uneducated or negligient. The worries that we have today are mostly significantly different to the worries that millenias ago and this is symetrically corresponding to the ever increasing advent of technology. The fear of serial murderes decreased to the advent of monitoring technology. The fear of not having enough food for drought season is greatly cut by the advent of refregiration technology and higher efficency in agriculture and farming to the point that we can distribute food evenly rendering unfavorable weather conditions to be irrelevant to our satiation and food supply. The fear of flood from occuring has greatly decreased as we understood the nature of such disaster and flood prevention systems. The fear of volcano eruptions has decreased as we can detect days or weeks prior eruption. We need not to resort to shamanistic beliefs or rituals such as sacrificing our third child to the volcano in hope of to prevent an earthquake and for us to have a prosperous harvesting season so that we can feed the people in our city. Nor circumambulating archaeological around a firepit when a baby is born in hope of to weed off evil spirits that can cause sickness and diseases to the baby.

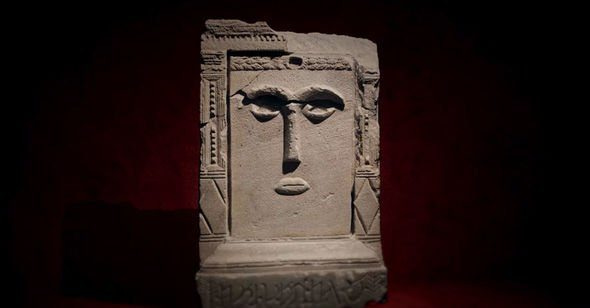

Though, we must not look down to people before us as they are simply "trying to figure things out" with their self-reinforcing belief system were made so that any outcome that reveals itself, will be feed back right into the system so that they can feel another taste of hope. They desperately need to be right, because if they had stopped hoping and stopped creating assumptions on how the world work, they would lost their one and only edge as a species, and that is to assimilate thoughts into actionable items that are against their extinction. It obviously doesn't mean that they are right with their assumptions, in fact two million people that lived in the Arabian Peninsula in 600 BCE with its archaeological evidences were polytheists are wrong. To go more futher, the oldest recorded civilization known as the sumer emerged in Mesopotamia (modern-day Iraq) in 3100 BCE developed the earliest writing system known as cuneiform that is found from 3100 BCE to 200 BCE. They were found to be polytheist and believed in Moon-God (Nanna), Sun-God (Utu), Wind-God (Enlil), Water-God (Enki), Fertility-God (Ishtar), and 3600 more. We are not going to dive in for every god in details, though we will explore on how it can be an objectively useful thing to believe in these God at the time.

They do not just pull 3600 Gods out of their asses, each God was written or came into being through careful analysis and lore attached to it on how it can help with their belief about the world. These Gods do not need to appear before them but rather is as an anthropomorphisation (to attribute human form or personality to things not human) of things that they couldn't describe otherwise. When situated in a condition where you can't explain the things around you, it is only natural to create assumptions, the intensity of one's desire for the assumption to be true correlates to the strength of the belief. As the beliefs are passed down to generations, assumptions that were once a mere myth became facts, especially if there is an appearing beneficial causation in believing the myths.

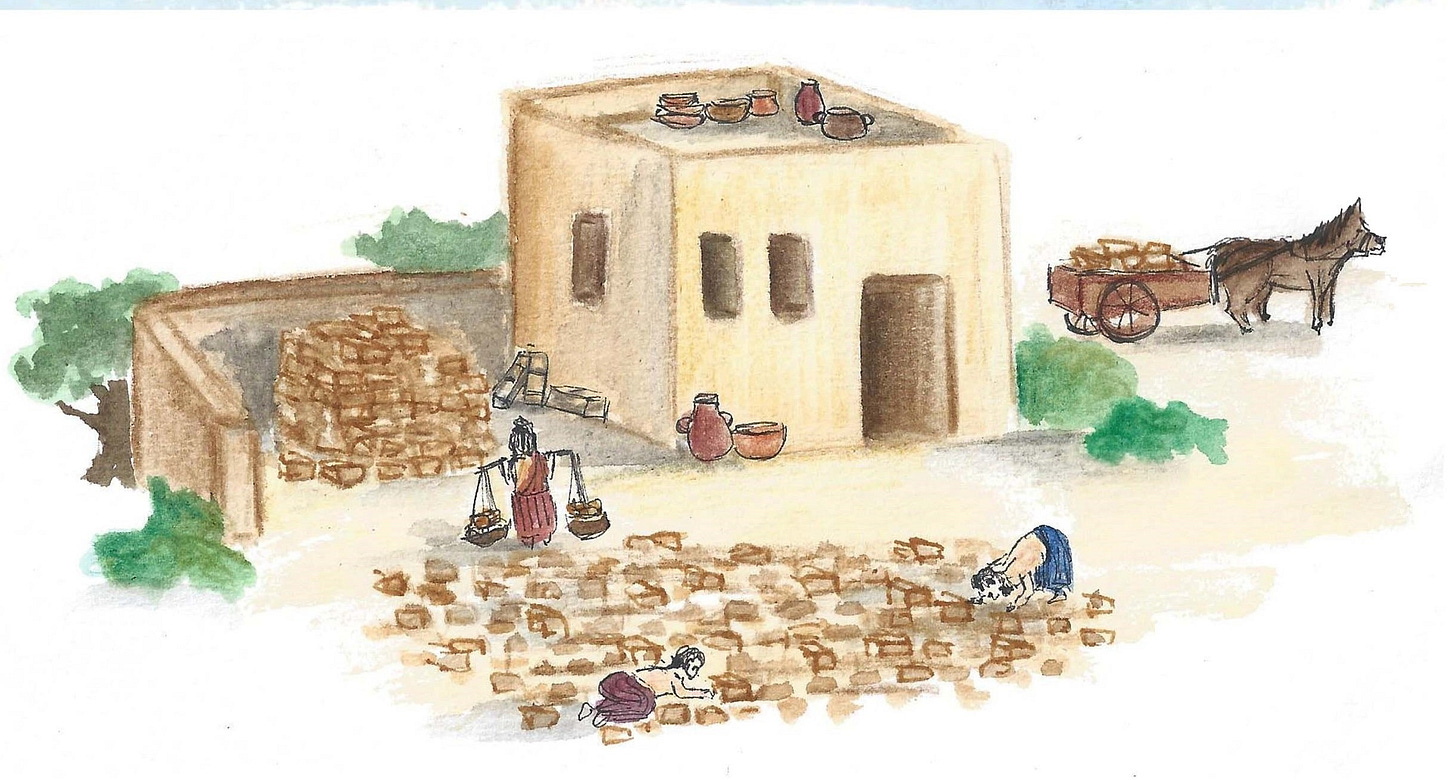

Imagine you are living in 3100 BCE in Southern Mesopotamia. Imagine a desert perhaps, your house is made of "Sun-Dried Mud Bricks" and so does is everyone. It is made by mixing clay, sand, straw, and water, then shaping into rectangular bricks and drying them in the sun.

As you can imagine, we already have an issue. If it rains, we are at least anxious about the durability of our home, we can take a bit of rain but not so much as it is literally capable of breaking our house down. The most common diet here is bread, and it's already hard to imagine how much we need to allocate our resources every day and accounting different seasons that the harvest may not always be plentiful. Social structures exist as well, even in 3100 BCE you can't just slack around and expect something to be handed to you, people who were born rich and got it all figured it out exists also. To make things worse, it actually follows right-skewed (Pareto) distribution, meaning a small elite controlled most of the wealth, while the majority of the population had little economic power. In Sumer, in Sumer: In Sumer, a tiny ruling elite consisting of kings, priests, and nobles controlled most of the wealth, land, and power, shaping the political and economic landscape. Below them, a small merchant class accumulated moderate wealth, benefiting from trade and skilled professions but still operating under the influence of the ruling class. Meanwhile, the vast majority of the population—farmers, laborers, and slaves—lived in poverty, struggling to meet their basic needs while supporting the elites through agricultural production, construction, and temple work.

If you are fortunate, you can eat meat from time to time, but as you can imagine, it became a difficult ask to have meat every day without referigaton and accounting the shelf life of a butchered lamb could only last for around 6 hours! Accounting the growth and reproductive cycle of lambs it became more and more unfeasable your lavish lifestyle as the majority in Sumer! Though, you should still be grateful to live in the civilization because essentially, no one is forcing you to stay, but you know better that these tasks of surviving is much harder to do if you just leave the civilization, from brick placing, staying away from predators and making sure your daily meal/hunt is consistently succesful for at least 2 times a day is a hard ask to do alone.

It seems that for us in order to live as a species, we are so biologically "out of edge". We are so biologically out of edge in terms of very little to no "biologically beneficial to consume natural resources attributes." We don't have sharp fangs, toxic saliva to easily digest meat, claws to cling on a running away prey, nor even the enzyme to consume raw grass and leaves.

We worry about food as much as any other species, that's why species come and go. As our biological edge lies in organizing and thinking, we tried our best to rationalize our environment for the sake of increasing our chance for survival, not because we want to but because we need to. In short, they too are motivated by the fear of death to rationalize their complex place in existence. That's why their 3600 gods seem bonkers because now we know that there is no way that there is 3600 gods and now since all of their believers are dead now we know that they were wrong. What I see is that it doesn't really matter if they were wrong, they were simply creating assumptions and as long as their assumptions helped them survive and to the point from the earliest civilization to date up to now, they did a pretty good job helping the human genome to pass through and down to us, and that is to be appreciated.

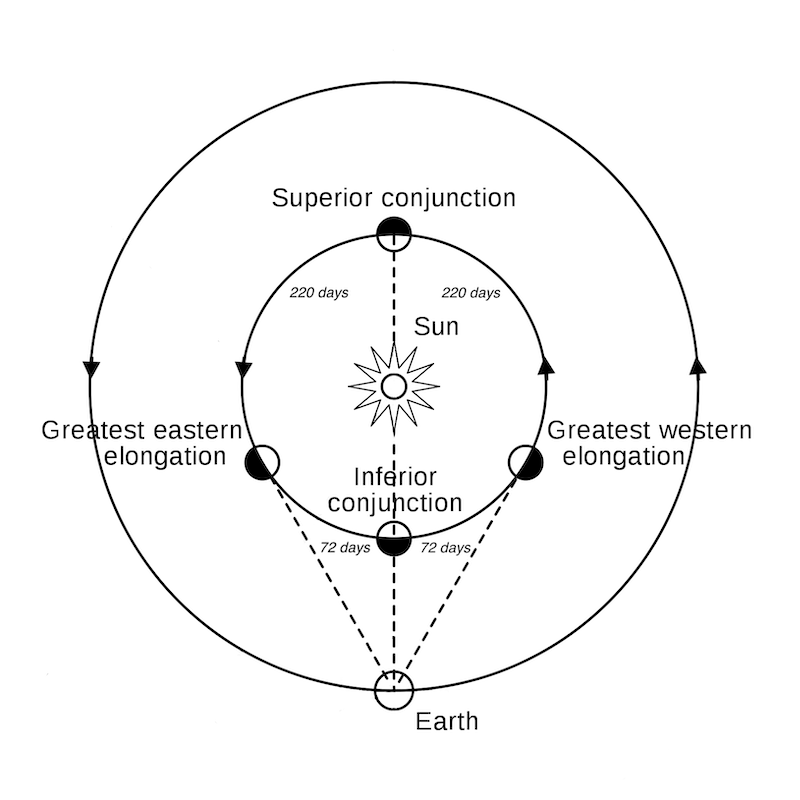

Now you will learn how the ancient Gods of Sumer were false but useful to believe in their daily life. In a world without light pollution, people can see the stars and so can the Sumer. As The Sumer gazes at the night sky, it observes a pattern that appears night to night, at that is constellations and constant appearances and disappearances of certain stars. One of it is actually the planet Venus that appears as a star. It would shine brilliantly in the early evening, then vanish for weeks, only to reappear before sunrise. This cycle was predictable, and they connected it to the world, linking it with the goddess Ishtar, the deity of love, war, and fertility. The timing of Venus’ reappearance in the sky often coincided with important seasonal shifts, marking the start of planting or the time for harvest. Over time, these patterns became a divine calendar, guiding their agriculture and religious ceremonies.

When Venus disappeared in the summer (Superior Conjunction), it aligned with the peak of the dry season in Mesopotamia. This was a time when harvests had already been completed, and the land turned barren under the scorching sun. The disappearance of Venus into the underworld mirrored the death of crops and the lack of rain. For Sumerians, this was a time to store grain, ration food, and prepare for water shortages.

Later in the year, when Venus disappeared in winter (Inferior Conjunction), it signaled another transition. This period of invisibility lasted for about 8 days, aligning with the seasonal shift towards the rainy period. When Venus reappeared as the Morning Star, it coincided with renewal and the planting season. Farmers saw this as a divine sign that the earth was ready to receive seeds, and water would soon be abundant again. The appearance of Venus in the morning sky marked the official start of planting, as it was seen as an indicator of fertility and the return of life. The re-emergence of Venus was celebrated as the moment when the land would become fertile once more, ensuring a successful growing season.

The reason Venus disappears at these times has to do with its actual position in space relative to Earth and the Sun. Superior Conjunction occurs when Venus is on the far side of the Sun, completely obscured from view. This happens because Venus orbits closer to the Sun than Earth, meaning there are periods when it moves behind the Sun from our perspective. At this moment, Venus is farthest from Earth and completely hidden in the Sun’s glare for about 50 days.

In contrast, Inferior Conjunction happens when Venus moves directly between the Earth and the Sun. This makes it invisible for a much shorter period, around 8 days, before it reappears as the Morning Star. During Inferior Conjunction, Venus is actually closest to Earth, but its brightness is overwhelmed by the Sun’s light, making it impossible to see.

From this case, you see now how believing in myths proven to be helpful for the Sumer survival. The Sumer live and died believing there's a God called Ishtar that appears and comes back every now and then providing a chance and signal the Sumer on what to do to maximize their chance of survival by being obedient to the Gods. In a sense, they perform certain actions based on observed phenomena about the world and try to make sense of it by anthropomorphizing it. The same flow of thoughts are observed on how they try to make sense of fear of thunder for example.

When a thunderstorm occurs, the Sumer believe that Enlil, the God of Wind and Storm is fighting with Asag, the Demon of Disease and Chaos. It gets more interesting as later civilizations has similiar concepts regarding the story. Now we know that the Babylonians & Assyrians, it's actually Marduk, God of Storm is fighting Tiamat, a primordial chaos dragon for them. In Ancient Egyptians, it's actually Set/Ra vs Apophis/Apep, the eternal serpent that tried to devour the sun each night. In Ancient Greek, it's actually Zeus vs. Typhon, a monstrous serpent-dragon who tried to overthrow the gods for them. In Norse, it's actually Thor vs. Jörmungandr, the thunderstorms were the sound of Thor riding his chariot and fighting giants.

I also want to state an important part the cause of the longetivity of belief is actually due to the infallibility. From the two examples, how Venus-God and Storm-God are practically infallible, because they take an observed fact, then anthropomorphizing it. Yes Venus "star" actually appears and disappear in the sky but there is actually no way of proving that Isthar is actually what lingers as the star. Same applies with the other 3600 Gods. Though the truth bares very little influence towards the believers. It is their way of life, it is important for their social cohesion, control, and most importantly, survivability. The Gods could also be as a reason for things that are otherwise unreasonable, for example earthquakes, floods, death of a loved one, miscarriages.

Impact of Beliefs