This article aims to explain how human life and society revolve around maximizing each individual’s well-being—a never-ending collective desire for improvement, comfort, and the pursuit of happiness, which inevitably results in relentless technological and luxurious progress, often at the expense of the less productive.

Humanity chisels itself in pursuit of perfection, weeding out the unproductive—not out of immorality, but simply because, at face value, this has always been the way for any animal to survive.

Morality is neither wired into nor promised to humanity; it is something humanity chisels into itself.

No one promised anyone a rose garden.

Table of Contents:

Advent of Cloth and Needle.

Theodore Kaczynski, the man who rejected the techno-industrial society.

Advent of technology and trade as a mean of subsidizing needs.

Trust and Trade: Civilization’s First Complaint.

It's not a rigged game.

Why Hypercompetition is being written.

Writer’s Final Note

Advent of Cloth and Needle.

If I ask you, take your whole family with you and imagine that you live 300,000 years ago in any place in the world, then how many days do you think you need to be able to create a needle and piece of cloth? How many months will it take? Or even years? Or maybe more than one lifetime?

The earliest fossils of homo sapiens were found in 300,000 years ago. Let that sink in, and needle as the tool to sew animal fur into clothing is only found 50,000 years ago. Now pay attention to the clothes that you are wearing and the needle marks that are visible, the 250,000 years of uncountable families that went about without the luxury of comfortable clothing to wear. Clothing that you don't even sew yourself. It's probably not even made near you. Yet you have it without even needing to know how the clothes were made, who made it, and how long does it took to create it. Wearing something that even yourself would take multiple lifetime just to produce the technology to create it.

Clothing is only one piece of under-appreciated produce of technology, now imagine that anything that came to the advent of sewing. Your bed sheets, pillow sheets, towel, bag, backpack, car seats, curtains, even the very surgical masks that saved lives—all of it, offshoots of that tiny, unassuming needle. A tool so simple, yet so powerful, it carved its place in the slow, grinding march of civilization. And yet, today, you can buy a set of them for a dollar without a single thought spared for the millennia it took to get here.

This is the curse and blessing of technological progress: the distance it creates between effort and outcome. The more advanced our world becomes, the less we are asked to understand it. You don’t need to know how to tan leather, forge iron, or stitch a wound. The knowledge has been externalized—outsourced into systems, machines, and invisible hands. In return, you're free to think higher, aim wider, dream faster.

But not everyone is caught in that upward current.

The world that rewards efficiency and innovation does not wait for those who lag behind. Comfort, wealth, and access flow to those who produce value—or are born near it. Those deemed “unproductive” in this brutal meritocracy aren’t given space to simply exist. They are rendered invisible. Not out of cruelty, but because the system we’ve built has no space for stillness.

It's not a conspiracy. It's not even necessarily immoral. It's just… nature, wearing new clothes.

In the wild, a sick antelope gets eaten. In civilization, an unproductive person gets priced out, laid off, replaced by automation, or ignored. Morality enters the frame only when someone—an individual, a group, a society—decides to say, “Maybe we should slow down. Maybe not everything should be about speed, scale, and surplus.”

But that’s rare. Because comfort is addictive. Progress is intoxicating. And survival, dressed in the language of profit and innovation, still carries its fangs.

And so, here we are—draped in convenience, lulled by frictionless living, surrounded by magic we don’t understand. The lights come on, water pours from metal faucets, food appears at our doors. The cost of this miracle? Someone, somewhere, was made invisible. And now, increasingly, it’s not someone—it’s everyone who falls outside the engine of optimization.

The lightbulb at your room can turn on and off on demand is a produce of two of humanity's greatest inventions:the manipulation of electrons, and the ability to extract energy from fire and coal.

Electricity is not some arcane substance trapped in wires. It’s the movement of tiny, invisible particles—electrons—nudged along by potential differences. That means we found a way to control, harness, and move the very things that orbit atoms. Something you can’t see, can’t touch, but is now pouring through your walls, powering your computer, cooling your fridge, and even keeping your heart beating if you rely on a pacemaker.

We did not just find electricity—we engineered entire civilizations around it. We designed languages (binary), systems (circuits), and infrastructures (power grids) to give it meaning and direction. Every modern convenience begins with this quiet, unseen flow of electrons.

But where do they come from?

We burn rocks (coal). That’s it. We dig into the Earth and pull out ancient, compressed biomass—coal—and set it on fire. The heat turns water into steam. The steam spins turbines. The turbines move magnets around coils of copper. And just like that, electrons start flowing.

You flip a switch in your bedroom, and somewhere, hundreds of kilometers away, a turbine spins because a billion-year-old carbon relic is being incinerated for your comfort.

You’re sitting in the present, powered by the death of the prehistoric.

You’re not asked to know the thermal efficiency of a steam turbine, or how alternating current differs from direct current. You just plug in and live. You inherit the miracle without knowing the myth.

But that comfort? That power?

It doesn’t just illuminate your room. It casts a long, harsh shadow over those who can no longer keep up.

You see, the more seamless our systems become, the more violently they reject friction. And friction, in a human sense, is anyone who cannot adapt fast enough—anyone who is slower, older, poorer, less educated, less wired in, or simply born on the wrong patch of Earth.

The modern world is powered not just by electricity, but by invisibility. You don’t see the coal miner. You don’t see the technician at the substation. You don’t see the logistics chain that brings the copper wire to your wall or the lithium in your phone. And just like that, we’ve extended that logic to people: if they aren’t “plugged in,” if they don’t contribute to the voltage of society, we don’t see them either.

The so-called “unproductive” are treated like power loss—leakage in the circuit. Not evil. Just inconvenient.

And it’s not always by cruelty. Sometimes it’s just optimization. A company doesn’t need a hundred clerks when a single software can do the job. A bank doesn’t need tellers when an app can handle deposits. A factory doesn’t need line workers when robots don’t sleep, strike, or forget to clock in.

People fall through the cracks not because someone pushed them—but because we’ve paved over the cracks with touchscreens and efficiency metrics.

And as that invisible infrastructure grows—algorithms deciding loans, job filters scanning resumes for keywords, housing applications judged by credit scores—your survival is increasingly determined by how visible you are to the system. Can you prove your worth? A degree? A clean record? Can you answer appropiately to the HR when they ask "Tell me about yourself? (That fits to the company's vision)?" Tell me who you are and how you can belong here.

If not, the system doesn’t punish you.

It just doesn’t see you at all.

You don’t get a seat at the table. You don’t even get told there was a table to begin with.

And yet, the lights stay on. The machine keeps running. Because comfort is self-reinforcing. Those who benefit from the system have little incentive to question it—and those who are excluded often lack the tools to fight back.

We’ve built a world that works so well, it no longer needs to care.

And here’s where the damage seeps beneath the surface—into the mind, into the soul.

Because when a system doesn’t see you, long enough, you stop seeing yourself.

You start to wonder if your worth really does boil down to productivity. You start measuring your days in output, in checkmarks, in whether or not you’re “adding value.” You scroll through lives that seem optimized and curated, while your own feels like dropped packets in a network too fast to care.

When survival was tied to physical danger, the threat was clear: get food, stay warm, don’t die. But now? The threat is existential. You don’t fear being eaten by a lion. You fear being forgotten—your life fading into the white noise of systems that don’t need you, that never even registered your presence to begin with.

And that absence of recognition? It corrodes you.

Because humans are wired to belong. That’s not philosophical fluff—that’s neurobiology. Our brains reward us with dopamine and oxytocin when we feel seen, accepted, integrated. It's a survival mechanism. In the wild, to be cast out of the tribe meant death. So our minds evolved to crave inclusion, attention, affirmation—not out of vanity, but out of necessity.

Now, imagine living in a world that tells you—through silence, rejection, automation, indifference—that you are surplus to requirements.

You’re not just unemployed. You’re un-needed.

You’re not just off the grid. You’re off the map.

And now it seems to me, it is at everyone's cost to actually be on the grid. Whilst at the same time there are annoying gurus who think otherwise whilst selling courses that keeps them on the grid. Your walmart is on the grid. Any meal that you eat without needing to hunt an actual animal is by all means declaring that you are on the grid.

Theodore Kaczynski, the man who rejected the techno-industrial society.

Before we go further, it’s worth confronting one of the most radical voices that ever pushed back against this system: Theodore Kaczynski.

Now, to be absolutely clear—this is not an endorsement of his actions or a romanticization of violence. Kaczynski committed horrific crimes, and nothing about his methods can or should be defended. But dismissing his entire perspective outright would also be a mistake. Ideas don’t become invalid simply because the person who spoke them committed atrocities—though they certainly become harder to wrestle with.

Buried in his infamous Industrial Society and Its Future is a lucid and alarmingly prophetic critique of how technological progress can erode freedom, increase dependence, and reshape society faster than our moral frameworks can keep up. Kaczynski argued that even well-intentioned technology isn’t neutral—it creates systems of control, consolidates power, and rewards conformity, all while quietly reprogramming what it means to be human.

“When a new item of technology is introduced as an option that an individual can accept or not as he chooses, it does not necessarily remain optional.”

— Kaczynski, Paragraph 127

And he wasn’t wrong. Try existing today without a smartphone. Good luck hailing a ride, logging into your bank, verifying your identity, or even accessing basic healthcare portals. What starts as “optional” becomes mandatory through slow, systemic pressure. Technology evolves from optional to mandatory infrastructure, and opting out begins to look like self-sabotage.

“Once a technical innovation is introduced, people usually become dependent on it and cannot simply choose to reject it if it turns out to have undesirable consequences.”

— Paragraph 52

Let’s take the car.

At first glance, the car looks like the ultimate tool of freedom. Go anywhere, anytime. Total autonomy. But the moment enough people own cars, the very design of society bends to accommodate it. Roads widen. Cities sprawl. Sidewalks shrink. Suddenly, not having a car doesn’t mean opting out—it means being excluded.

You no longer get to “choose” whether to drive. You must.

The job you want? Two hours away by highway. The grocery store? Twenty minutes on roads with no pedestrian path. You are not free because of the car. You are trapped by it.

And the costs? Baked into your life. You pay for gas, for insurance, for parking, for registration, for repairs. You spend thousands of hours stuck in traffic. You inhale polluted air from millions of other people doing the same thing. You destroy the environment to maintain the illusion of movement.

“The technophile may object that if people didn’t like cars, they could stop using them. But this is a naive oversimplification.”

— Paraphrased from Paragraphs 58–60

Cars didn’t just replace horses. They reshaped civilization. Try getting your kids to school in a suburb without one. The freedom offered by the car only exists if you accept the terms and conditions: a sprawling infrastructure, endless consumption, and dependence on fossil fuels.

It’s the same pattern Kaczynski warned about: technology solves a problem in the short term, then creates a new system that makes opting out impossible.

But here’s the thing: Kaczynski’s conclusion was that civilization must be torn down to preserve human freedom. That’s where his logic collapses. The problem he saw may have been real—but the solution he pursued was pure destruction.

In this light, Kaczynski becomes a cautionary tale not just of extremism, but of what happens when legitimate discontent meets isolation, rage, and absolutism. The questions he asked deserve attention. The path he took is precisely the one we should not walk.

I think, he fails to see that techno-evolution is inevitable, it's an unstoppable force driven by humanity's desire for comfort that folds itself towards the advent of technology.

Advent of technology and trade as a mean of subsidizing needs.

Imagine you are living in 3100 BCE in Southern Mesopotamia. Imagine a desert perhaps, your house is made of "Sun-Dried Mud Bricks" and so does is everyone. It is made by mixing clay, sand, straw, and water, then shaping into rectangular bricks and drying them in the sun.

Your village is near a river, which floods annually and leaves fertile soil behind. That means you can grow more grain than your family needs. You store the extra. Then something strange happens. Instead of just surviving, people begin to specialize. One person makes pottery. Another tracks the stars. Another oversees irrigation canals. A class of people emerges whose job is not to gather food—but to organize it, to measure it, to record who owes what to whom.

This is the birth of trade. Not just in goods, but in abstraction—value, debt, labor. You trade your surplus barley for someone else's goat milk. They trade that for someone’s wool. Over time, the transactions become too many to remember, so someone invents a symbol. A mark. A tablet. Writing.

Suddenly, you don’t just need food. You need scribes. You need temples. You need rules and weights and systems. You need society.

Technology isn’t just fire and iron. It’s also the invention of coordination.

And as coordination scales, so does dependency.

No one person makes a city work. No one household makes its own bricks, grows its own food, makes its own tools, and stitches its own clothes. That’s the point. The entire arc of civilization has been to outsource tasks in the name of efficiency—and to consolidate power around those who manage the flow.

But here’s the thing: this structure only works when everyone plays their part.

Trust and Trade: Civilization’s First Complaint.

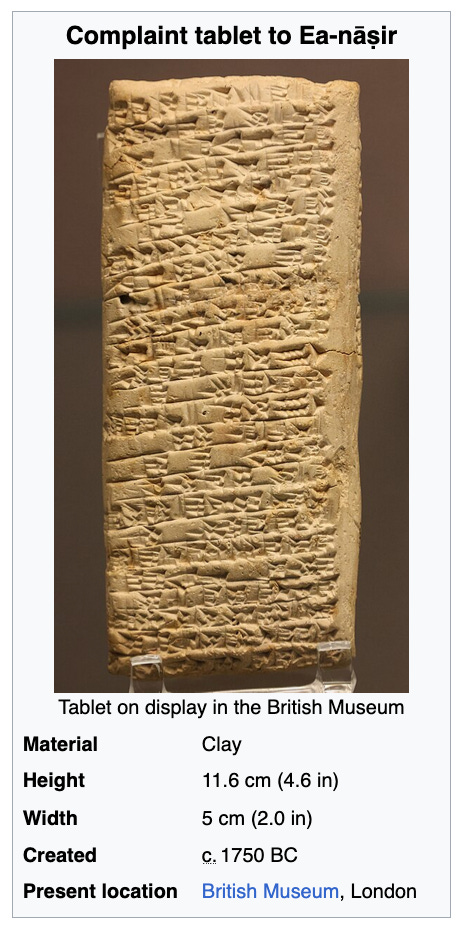

I'm not just talking shit when trade was already existing even from ancient mesopotamia. The oldest writing ever known in civilization is sumerian and the second oldest is the arcadian, we get to see the glimpse of earliest civilization from translating what they managed to write and one of the records show a customer complaint.

A clay tablet 4000 years ago, written in cuneiform by a man named Nanni, addressed to a merchant named Ea-nasir, found in the ruins of Ur in ancient Sumer. Nanni was furious. He had sent a servant to buy copper ingots from Ea-nasir. What he received was garbage—subpar copper—and a healthy dose of disrespect. [Nat Geographic]

“You have treated me with contempt by delivering ingots that were not good, and you said you would not take them back. Let me inform you that I will not accept copper that is not of fine quality.”

Imagine that. Thousands of years ago, some guy stomped back to his mud-brick house, fuming, and decided to immortalize his bad review in baked clay.

But beneath the comedy lies something profound: even 4000 years ago, people understood value, demanded fairness, and used writing as a weapon of accountability. This wasn’t just about copper—it was about trust in a system where interdependence had become a survival necessity.

Nanni couldn’t make his own copper. He relied on the merchant. The merchant relied on the transporter. And when that chain failed, it wasn’t just an inconvenience—it was a betrayal of a fragile civilization-in-progress.

So, we see: the invention of writing itself wasn’t born out of poetry—it was born out of the need to keep receipts. To log debts, track goods, resolve disputes.

That’s trade. That’s civilization. A network of expectations, trust, enforcement, and yes—complaints.

And it hasn’t changed much.

And while the medium has changed, the message hasn't: as soon as you depend on others, you also become vulnerable to them. Civilization is this double-edged gift—liberating us from self-sufficiency, but chaining us to structures we don’t control.

That complaint from Nanni wasn’t just a grumpy Yelp review in cuneiform—it was a signal flare from the dawn of civilization: "I depend on this system, and it failed me."

Now fast forward 4000 years.

You don’t trade barley for goat milk anymore. You swipe a plastic card or tap your phone. In return, a signal zips through fiber optics, pings a server farm, deducts numbers from one account, and adds them to another—possibly across continents. And in that blink of light, you’ve just bought a toothbrush made in Vietnam from an online store headquartered in Delaware using a credit card issued by a bank in Singapore.

You didn't see a warehouse.

You didn't see the cargo ship.

You didn't see the bank’s server.

You didn’t even see your own money.

And yet, you trust it.

That’s the miracle—and madness—of financial abstraction. The further civilization has progressed, the more symbolic the act of trade has become. We used to trade what we had. Then we traded representations of what we had (coins, then paper).

It's not a rigged game.

But here's the part people often miss—this isn't a rigged game. It's just how the game has always been played.

There are, really, only two ways to make a living in this world:

1. Work for a company that solves other people's problems.

2. Build a company that solves other people's problems.

All in all, society revolves around maximizing each individual sense of well being.

Not just vague desires—but urgent, felt needs.

Whether you’re stocking shelves, writing code, cleaning teeth, or designing rocket engines, you’re in the business of making someone else’s life better, faster, easier, or more fulfilling. You’re either making or enabling comfort, productivity, novelty, or survival. If you’re doing it well? You get paid. If you’re doing it exceptionally? You get promoted. If you do it at scale? You get rich.

And if you’re not doing it?

You get replaced.

Layoffs aren’t personal. They’re cold arithmetic. A company exists to solve problems profitably. When your role no longer contributes to net positive value—when automation, outsourcing, or shifting priorities make you redundant—the system cuts. Not to punish. But to survive. The company's lifeline is maintaining healthy cashflow afterall.

This is the ancient loop of civilization: solve a problem, do it better than anyone else, and people will give you what matters most—their attention, their time, their money.

From the first potter who shaped better jars, to the first merchant who figured out irrigation schedules, to the coder who builds a SaaS tool that saves companies $1 million a year—the arc is the same:

Understand what someone needs. Deliver it better than the alternative. Repeat at scale.

That’s it. That’s civilization.

Empires weren’t built on vibes. They were built on specialization, trade, and problem-solving at scale.

Which is why entrepreneurship is not a rebellion against the system. It is the system. The purest form. The rawest feedback loop.

This is what people often misunderstand about the modern world. It’s not that technology destroyed jobs. It’s that technology revealed just how fast we can adapt to better solutions. And when you see the world this way, layoffs and restructuring are not signs of collapse. They’re symptoms of evolution.

They make space. And in that space, the courageous build.

So if you ever feel crushed by the system, understand this:

The system isn't telling you to give up. It's telling you to be something that people need.

The rule of the game remains elegant in its simplicity:

If you can help others live better, they will reward you.

This isn’t just capitalism. It’s not just business. It’s humanity, scaled up.

So whether you're working a job, launching a product, freelancing, coding, planting, designing, or fixing pipes—you're part of the grand, messy experiment of progress. You’re one node in the system trying to push a little more value into the world than you take out.

My CFO at one of his presentation once said:

A purpose of a company is to generate more revenue than its cost. This is the life and death of a company.

A very simple truism but somehow it stuck to me that it applies not only for a sole company, but apparently as much as an individual human couldn't possibly live alone but will need a help of his/her tribe, it feels that it pretty much applies to us as an individual human being.

This is why value-creation, matters so much. Because it’s not just about building wealth—it’s about building meaning.

It’s not just about what you're paid to do.

It’s about who you become when you realize you can solve something for someone else.

Every successful business, every satisfying job, every purposeful life shares this common DNA: it starts with noticing a problem that isn’t being solved well—and saying, “I can do that.”

Why Hypercompetition is being written.

I was inspired to write hypercompetition when I was watching a youtube video on how 2030 ish AI would seem to replace more and more jobs as it feels with certainty that it is only a matter of time that we scrape off list that what AI can't do.

I experienced this firsthand while working in cybersecurity, where AI had already proven itself helpful in doing my job. Writing "compliant scripts" that check specific parameters of an operating system to ensure the AWS infrastructure is impenetrable by hackers is a tedious job and requires extensive monitoring on the latest cybersecurity hacks and patches. I was initially writing the compliant scripts in bash and powershell manually which requires first understanding what my code can do to prevent a hacker from possibly harm our system, I started asking ChatGPT to help write my code. It wasn’t great at first as I still need to manually fix the code after it gave it to me but it still helpful nonetheless, to the point where I could receive e a fully functioning code just based on one prompt and then I can also actually create a system to do the test for me. The discovery of recent vulnerabilities updates itself pretty recent too and me working for a banking company, security vulnerability is non-negotiable, to the point that we need to find a way to somehow automate the whole workflow of compliant scripts creation to testing as soon as a new vulnerability is discovered.

I went from writing compliant scripts to prevent vulnerabilities in the OS and doing the test myself that usually take days to weeks to write a handful of scripts to automating the whole workflow which results in creation and testing takes a few hours. My salary did not increase nonetheless, my work is still arithmetically counted in per hour basis. I hold no grudge in this, It just reminded me on how fast AI has come and it sort of inevitable for the newcomer that were to apply for my current position needs to be more gifted than what AI can already do. It's something that is entirely impersonal from the company's perspective, it's just a value-driven market.

A company never cares about the rate of unemployment of a country is X percent. If anything, they are probably having a thousand or more applicants. They simply couldn't accept everyone who applied.

But here’s the twist: the same system that forgets you will remember you, if you show up as someone who helps others.

Not just in grand, heroic ways. But in the daily act of noticing a need and meeting it. Making things a little clearer. A little kinder. A little more useful. Whether it's a bug fix, a warm meal, a line of code, a thoughtful message, or a business that lifts others up—that’s your voltage. That’s how you stay wired in.

And it’s not just how you earn a paycheck.

It’s how you reclaim your name in a world that forgets people fast.

Because in the end, you’re not just a node. Not just a metric. You’re a story—complex, invisible until seen, invaluable once understood.

And maybe that’s the quiet hope in all this hypercompetition: that beneath the algorithms and automation, beneath the layoffs and upgrades and optimization charts, there’s still a chance to be needed—not because you’re fast, or flawless, or frictionless—but because you cared enough to solve something that mattered.

That’s how you stay visible.

Not by screaming for attention.

But by becoming someone whose absence would be felt.

Writer’s Final Note

Hypercompetition is a really cold, sad but true article. I think for humanity’s longer time, its nice that we are able to do both building our home from sun-dried clay and feel comfortably that we are still going to eat without needing to go to hunt, division of labor seem digestible and we understand it more easily that its necessary.

As the world turns to be more modern, the nuances sort of disappear. Now people beginning to doubt that their jobs are really the thing that they want to do. Technology such as cars, road pavements, houses have become so much more advanced that it has become not optional to opt out. I guess the most painful part is that we never really have a say in this or even in any of these things. We were born and raised faster than we can see our available choices and raise a meaningful passion, we are not born w passion as much as we don’t get to say how long should our traffic to our job takes time, we are melted into it. We, our identity, if shaped by what we do, shaped by the time we took, are melted to the world that we live in.

It never really changes that much as a farmer’s son in 3000 BC have very little to say that it won’t become a hunter because it lacks the education and equipment to hunt, we are also born in a world where disadvantages just from where you were born exists.

All in all, the emotion as a reaction from seeing the world as it is remains ours and it will always be ours.

Competition maybe used to be healthy where everyone gets a good part of the pie, but as we go by, it seems that hyper-competition as there are seemingly way lot more people or systems are better by doing the job that you wish to be in, layoffs are just inevitable.

But it all stems from the same principle that all enterprise is just a group of people striving to create more than they take in. And now it has become a requirement for everyone that is brought into this world with already existing luxury, tech, wonders of electricity baked into it. They need to be able to create more than they take in.

It’s not just a price for admission, but it also comes with a freedom of choice to which division you wish to take part in. We may have very little voice to opt out, but to adore and participate in creating a more awesome world is just a luxury in itself.

really enjoyed reading this piece !! you present such interesting ideas in such a clever way, can’t wait to read more of your work :))

Adding to my night read list.